By Pejman Akbarzadeh

BBC Persian Service (13 Sep. 2024)

Soudabeh Tajbakhsh, one of the most renowned singers of the Tehran Opera Company, passed away in anonymity in Munich, Germany, on August 15, 2024. She was 95. Her death is now being announced for the first time through the media, more than three weeks after it occurred.

Since the founding of Rudaki Hall and the Tehran Opera Company in 1967, Tajbakhsh starred in many of the company’s most notable productions. However, her career came to a halt following the 1979 Islamic Revolution in Persia (Iran). She spent the last 45 years of her life quietly in Munich.

Soudabeh Tajbakhsh was born in Tehran in 1929. Her uncle, Gholam-Hossein Banan, was one of the most celebrated Persian singers of his time. Although her family encouraged her to pursue a career in Persian music, Soudabeh initially lacked the passion for it.

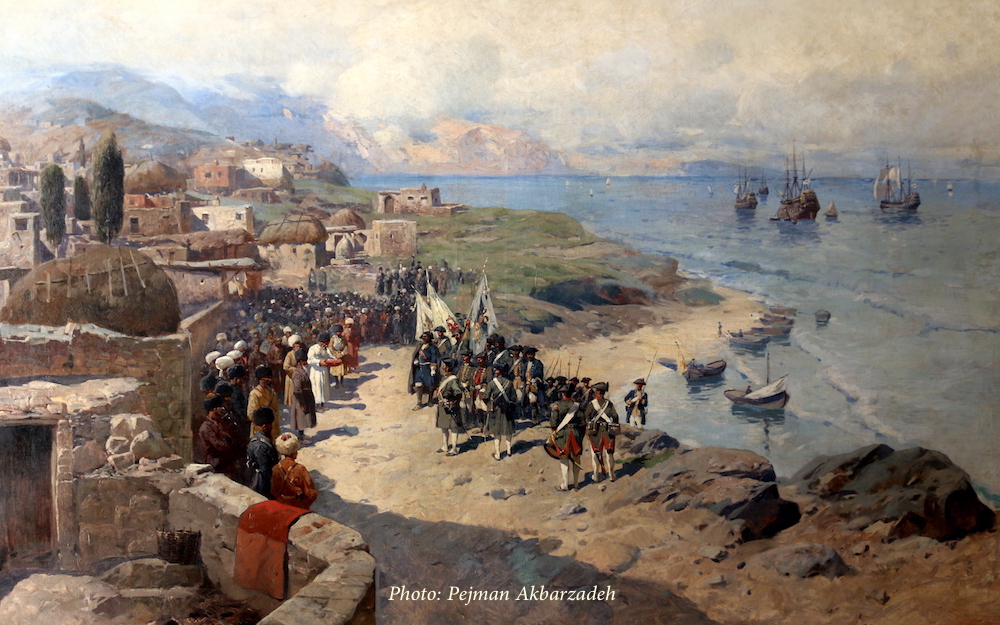

In 1947, when Soudabeh was just 18, a full opera was staged in Tehran for the first time, albeit with limited facilities. This was made possible by the efforts of Lili Bara, an Austrian opera singer who had taken refuge in Persia during World War II. Bara also taught at the Tehran Conservatory of Music but moved to the United States shortly after. Following her departure, Tamara Pilossian, a Persian-Armenian singer, began teaching at the conservatory. At that time, Tajbakhsh enrolled to study singing, but Pilossian also left the country after just one year. Tajbakhsh later continued her studies with Evlin Baghcheban at the Tehran Conservatory and, in the mid-1950s, moved to Germany to further her education.

At the Cologne Academy of Music (Musikhochschule Köln), Tajbakhsh studied under Joseph Meternich and Clemens Glettenberg. In later years, after she became a successful opera singer with the Tehran Opera Company, Prof. Meternich was invited to Persia to attend her performance in “Don Giovanni” at Rudaki Hall.

During her academic years, Tajbakhsh married Michael Rossos, a Greek opera singer who was working in Germany at the time. Their marriage resulted in two sons, Aris and Arman. The marriage ended when Soudabeh decided to return to Persia.

(Left to right: Culture Minister Mehrdad Pahlbod, opera singer Soudabeh Tajbakhsh, Empress Farah Pahlavi at Rudaki Hall, Tehran, 1968.)

Tehran Opera Company

After her studies, Tajbakhsh appeared as a guest singer in a few roles at Saarbrücken Opera in Germany, but her professional career truly began in 1967. In the spring of that year, after ten years away from her homeland, Soudabeh Tajbakhsh traveled to Tehran to visit her family. Her trip coincided with the state visit of the King and Queen of Thailand, and Tajbakhsh was invited to perform at Golestan Palace for the occasion. The Tehran-based English-language weekly “Iran Tribune” reported on October 25, 1968, that following the warm reception, “the Ministry of Culture officially invited Tajbakhsh to stay in Iran and work with the Tehran Opera Company.”

At the time of Mohammad-Reza Shah Pahlavi’s coronation in October 1967, Rudaki Hall, the most prestigious venue for performing arts in Persia, was inaugurated. For the opening ceremony, a Persian composer was commissioned for the first time to write an opera. Ahmad Pejman composed “Jashn-e Dehghan” [Rustic Festival], which featured Hossein Sarshar as the old peasant and Soudabeh Tajbakhsh as the village woman in the lead roles, directed by Enayat Rezai. No audio or video recordings of this historic performance are available. “All attention was focused on the coronation, and nobody paid attention to the opera itself,” Rezai lamented to the BBC Persian Service.

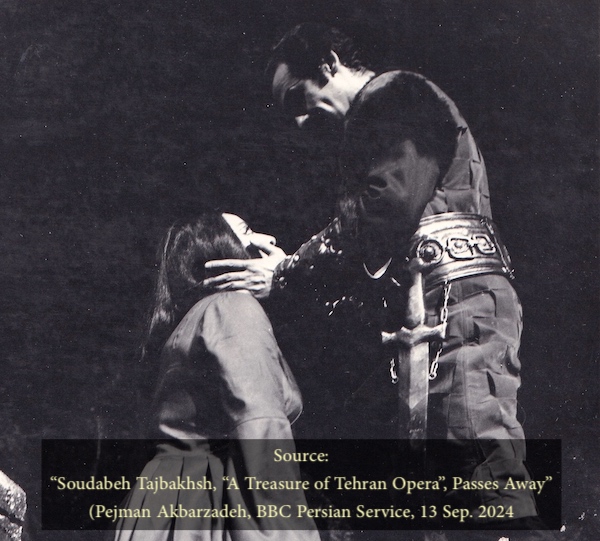

In 1968 the Ministry of Culture, again commissioned Ahmad Pejman to write a new opera “Delavar-e Sahand” [Hero of Sahand]. The libretto was inspired by the story of Babak Khorramdin, a 9th-century Persian revolutionary leader. Hossein Sarshar (Babak) and Soudabeh Tajbakhsh (Rokhsareh) performed the lead roles. An amature recording is available from the live performance and it seems the only available recording of Soudabeh Tajbakhsh performances at Rudaki Hall. Enayat Rezai who was the director of the Tehran Opera Company at that time says: “The operas normally used to be recorded by the hall. We were relieved the recordings are safe there. On the other side, as employees, we were not allowed to record the performances. Nobody imagined that sudden changes would happen in the country and we lost access to everything.”

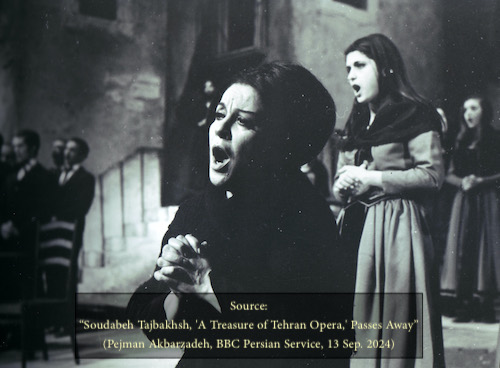

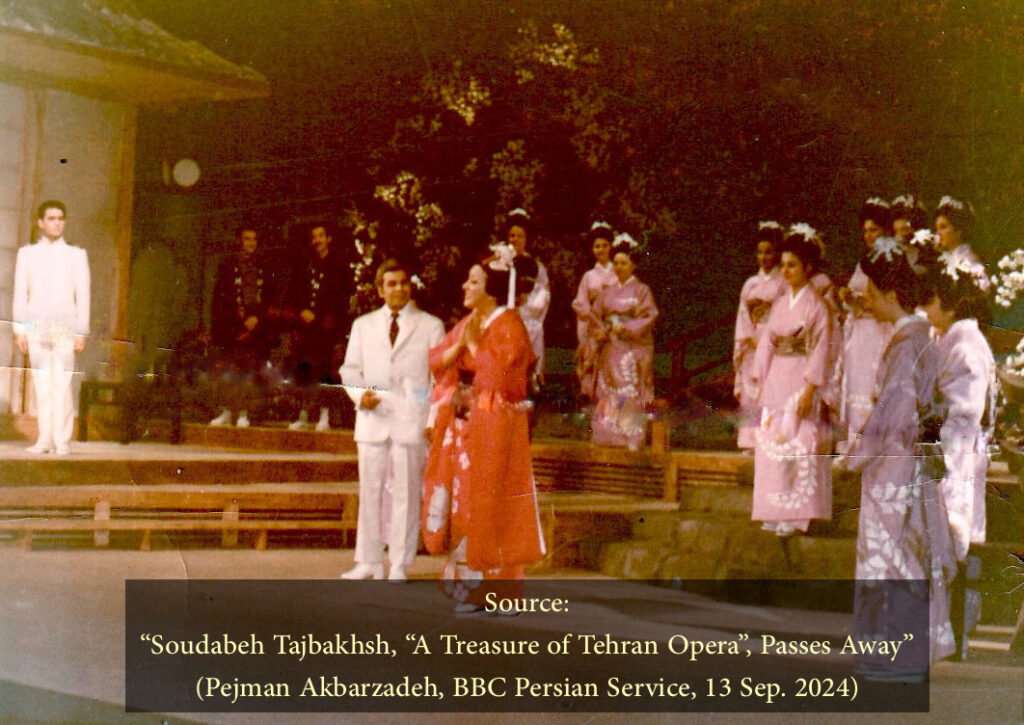

Regarding European operas, one of Tajbakhsh’s most notable performances was in Tosca, which was staged for the first time in Persia in 1968, under the direction of Enayat Rezai. The production, by the Tehran Opera Company, was warmly received by the media, with Kayhan International praising Tajbakhsh’s voice as a “treasure for Tehran Opera.” In addition to Tosca, Tajbakhsh starred in lead roles in La forza del destino, Turandot, and Madama Butterfly. Music critic Janet Lazarian of Ferdowsi Magazine hailed her as the “most successful female opera singer of the Tehran Opera” that season.

Enayat Rezai, who directed many of these operas, expressed regret that Tajbakhsh’s career did not progress as it should have. He noted that she possessed a dramatic soprano voice, ideally suited for Verdi and Puccini operas. “Her voice was both soft and powerful, with the ability to project across 300 meters without a microphone, a key requirement in opera. Tajbakhsh’s voice reflected the training she received from Professor Meternich, evident in its remarkable quality”, Rezai added.

Soudabeh Tajbakhsh as Cio-Cio-San and Enayat Rezai as Sharpless in a scene from Madama Butterfly, Rudaki Hall, Tehran, 1971-72 season.

One of Tajbakhsh’s relatives, who attempted to organize her private collection a few years ago, said: “Unfortunately, we couldn’t find any audio recordings in her collection. It was only a few years ago that we managed to persuade her to sing and record something in a church in Munich. We wanted to preserve that as a memento.”

In 1972, Soudabeh Tajbakhsh resigned from the Tehran Opera Company and moved to Germany. However, she was later invited several times by Rudaki Hall to perform as a guest singer. In one of these performances, she appeared as Senta in Wagner’s The Flying Dutchman, directed by James Conrad in 1976.

In September 1978, following the massive anti-government demonstrations in Tehran, events at Rudaki Hall were suspended. By February 1979, after the Islamic Revolution, the Tehran Opera Company was shut down. Tajbakhsh’s sister, Sousan, says, “Soudabeh’s salary from the Pahlavi Foundation was cut, so she began working at a bookstore in Munich. She could not continue her career and never returned to Iran.”

Soudabeh Tajbakhsh passed away on August 15, 2024, in Munich.

—

(UPDATE: The other roles Tajbakhsh performed at Rudaki Hall in the mid-1970s include Leonore in Fidelio and Elizabeth in Don Carlos.)

Related Posts:

The Days Tehran Had Opera

Celebrated Persian Composer Ahmad Pejman Honored in Los Angeles

From Persia to Pittsburgh: Composer REZA VALI Turns 70

A Century of Cello Music from Persia 1921-2021

Keywords: Opera, Rudaki Hall, Persia, Iran, Tehran Opera House, Persian, Iranian, Sudabeh Tadjbakhsh, Enayat Rezaei, Ahmad Pezhman, Pejman, Pahlavi Era, Mehrdad Pahlbod, Ministry of Culture Art, Fine Arts, Music